There are many possible factors which could initiate a vicious

cycle of pelvic floor muscle spasm and pain. Dr David Wise contends that

large numbers of patients develop CPPS as a result of chronically

tensing their pelvic floor muscles in response to stress and anxiety:

Quick Facts:

Quick Facts:

- Pelvic floor muscle spasm may be the main cause of symptoms in over 90% of CPPS patients. Everyone with CP/CPPS should have a pelvic floor examination as part of a complete urological work-up by someone expert in trigger point/myofascial evaluation.

- When found, pelvic floor muscle spasm and myofascial pain can be effectively treated.

Introduction

It is becoming increasingly recognised that the symptoms of abacterial 'prostatitis' and Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CPPS) may, in fact, have little to do with the prostate, but appear to be more related to chronic spasm of, shortening of and trigger point formation in the pelvic floor muscles. Studies show that the tissue inside the prostate itself is not significantly inflamed in over 95% of cases.In the April 2001 issue of the Urology Times, reporter Scott Tennant stated that "the very idea that the pain and symptoms of ('abacterial') prostatitis have little or nothing to do with the prostate may be foreign to many urologists". The recently published book by Dr Rodney Anderson and Dr David Wise entitled 'A Headache in the Pelvis' promoted the concept that pelvic floor muscle spasm may be largely responsible for the symptoms of abacterial 'prostatitis' or CPPS. Indeed, many men are now reporting significant improvements in their symptoms as a result of treating pelvic floor muscle spasm in the manner promoted in this book. So, what exactly is the relationship between pelvic floor muscle spasm and the symptoms of CPPS?

Do I have Prostatitis or

Pelvic Pain Syndrome (Pelvic Myoneuropathy)?

Although some studies find a minority of men with chronic pelvic pain have

little inflammation (as measured by white blood cells, or pus cells, in their

expressed prostatic secretions), other studies that look at more subtle markers

of inflammation (cytokines) find inflammation in the majority of sufferers.

The mystery is what is causing this inflammation? Infection is ruled out, although

work still goes on, fruitlessly at this stage, to prove that perhaps nanobacteria

or a stealth virus may be to blame. But recently work with mast cells and nerves

points to a more likely culprit: neurogenic inflammation triggered by muscle

spasm (discussed further below). We call this "pelvic myoneuropathy" (myo =

muscles, neuro = nerves, pathy = disease). In German "Myoneuropathischer

Beckenschmerz" (read how

we arrived at our descriptive new label for CP/CPPS). An even newer term

coined by the NIDDK in 2007 and that encompasses both male and female pelvic

myoneuropathy (CPPS and IC) is "UCPPS",

which stands for Urologic

Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (or

Syndromes).Pelvic Floor Muscle Spasm

The lack of any clear problem within the prostate itself has caused several researchers to look elsewhere for an underlying cause of CPPS. Urologists at the University of Colorado studied 103 patients with 'abacterial prostatitis'. When they palpated their patients' pelvic floor muscles, they found that 88% of these patients had "myofascial tenderness" in the rectal area which was associated with the inability to relax the pelvic floor efficiently. When they measured these patients' voiding behaviour with invasive urodynamics, they found that a whopping 92.2% of these patients had "dysfunction of the pelvic floor muscles". Therefore two key points to arise are (1) few CPPS patients have any evidence of infection in the prostate itself; and (2) the majority do have pelvic floor muscle spasm.The next question that arises is this: how does chronic spasm of the pelvic floor muscles cause the pattern of pain and voiding dysfunction typically seen in CPPS patients?

Pelvic Floor Muscle Spasm - what is it and how does it result in the typical symptoms of CPPS?

Anatomy and Function

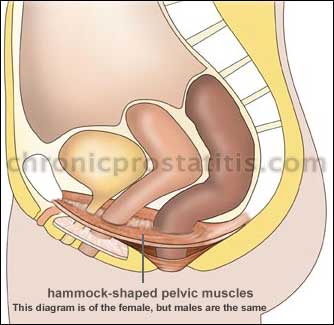

The first thing we need to appreciate in answering this question is the anatomy and function of the pelvic floor itself. As you can see from the diagram below, the pelvic floor is "slung like a hammock" at the base of the pelvis (a more detailed anatomy of the pelvic floor can be seen in this set of diagrams).

The pelvic floor consists of the pelvis [and] the levator ani muscles which go between the pubis and the sacrum. There are a central group of these muscles which surround the urethra and the rectum. Beneath this floor there are also sphincter muscles around the anus and urethra. The side wall's obturator internus insert on the pubic bone [and] can have some effect on the urethra.

Myofascial Trigger Points - Relationship to Pain Symptoms

The underlying causes of muscle dysfunction are myofascial trigger points, which are defined as a hyperirritable spots in the muscles that refer pain and are tender to touch. Physiotherapist Rhonda Kotarinos states that "these can be a source of pain as well as cause the muscle not to function properly". She goes on to state that trigger points are "usually caused by a muscle that is being overloaded and worked excessively". It appears that when the muscle is overworked, either by unconscious tensing of the muscle (usually because of anxiety) or due a protective/splinting muscle spasm, trigger points develop in the muscle. These can then cause pain in any part of the pelvic floor, creating wide ranging pain from the pubic bone to the perineum and coccyx. Psychologist David Wise feels that the pelvic muscles become chronically tightened in a trigger point (contracture), giving irritated tissues little or no chance to heal. This in turn, can lead to the symptoms commonly associated with CPPS.Relationship to Urinary Symptoms

It may be possible for muscles spasm and trigger points to give rise to urinary symptoms in a number of ways. Trigger points in the pelvic floor may have an effect on the bladder and associated nerves giving rise to urinary frequency and urgency and through the referral of pain to the bladder. Moreover, if the pelvic floor is unable to relax properly during voiding this will result in a weakening and "splitting" of the urinary stream. Dr Weiss states that there may be "more tension and constriction around the urethra... Therefore, symptoms can occur just because of tension". Also, there are muscles in the perineum responsible for contracting forcefully at the end of urination in order to "squirt" any remaining urine out of the urinary tract. If these muscles are in spasm or are unable to function properly, this may be one possible reason for the symptom of "dribbling" at the end of urination, and also for the commonly reported symptom of weak ejaculation.Relationship to Inflammation

Although the inner tissues of the prostate are rarely inflamed (as they would be if the prostate were infected), CPPS patients do have markers of inflammation in their prostatitic secretions, such as abnormal cytokine profiles in their EPS, and some have changes to the bladder wall or prostatic urethra indicative of active neurogenic inflammation.Chronically overstimulated pelvic nerves result in the proliferation and degranulation of mast cells, via neuro-mast-cell connections in the linings (epithelia) of the bladder and/or urethra and/or prostate, testes etc. Nerve endings in the genitourinary tract (bladder, urethra, prostatic epithelium, etc) release substance P and other neuropeptides/neurotransmitters that cause mast cell proliferation and degranulation, and release histamine, serotonin and prostaglandins. All of these substances irritate the surounding epithelial tissues and make the lining of the bladder/prostate etc. more permeable, thus creating the symptoms of the Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes (UCPPS, covering CP/CPPS, IC/PBS).

So nerves can cause inflammation, nerves can create trigger points, and trigger points in the pelvic floor feed back noxiously into the central nervous system in a cycle that perpetuates itself. Interrupting this cycle is key to recovery.

There are studies that support this concept. Szolcsanyi stimulated the spinal cord nerves in a rat that correspond to the bladder nerves and was able to create a neurogenic inflammation (that is redness, swelling in the bladder/vaginal opening and other pelvic organs). Lavelle stimulated the sacral ganglia and increased the permeability of the bladder lining in a rat to water and urea. Theharides found that psychological stress activates bladder mast cells. Therefore, by this mechanism, stimulation of the pelvic floor muscles can create the bladder wall changes. In other words, nerves and muscles can affect the genitourinary tract!

More recently, Apodaca et al have shown how nerves can disrupt the bladder lining, and there are studies showing how stress can cause inflammation in mammalian urogenital tissues. And in 1998, Doggweiler et al were able to create inflammation in rat bladders by damaging their spinal cords with a deliberately introduced viral infection of the spine.

Possible role of HPA Axis

The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis may be implicated in this cascade of events. Recent studies show that people with pelvic pain have abnormal HPA axis regulation, possibly due to an enzyme deficiency or stress.What can cause Pelvic Floor Muscle Spasm / Pelvic Myoneuropathy?

There are many possible factors which could initiate a vicious cycle of pelvic floor muscle spasm and pain. Dr David Wise contends that large numbers of patients develop CPPS as a result of chronically tensing their pelvic floor muscles in response to stress and anxiety:We have identified a group of chronic pelvic pain syndromes caused by overuse of the human instinct to protect the genitals, rectum and contents of the pelvis from injury or pain by contracting the pelvic muscles. This tendency becomes exaggerated in predisposed individuals and over time results in pelvic pain and dysfunction. The state of chronic constriction creates pain-referring trigger points, reduced blood flow, and an inhospitable environment for the nerves, blood vessels and structures throughout the pelvic basin. This results in a cycle of pain, anxiety and tension which has previously been unrecognized and untreated. Understanding this pain, anxiety and tension cycle has allowed us to create an effective treatment. Our program breaks the cycle by rehabilitating the shortened pelvic muscles and connective tissue supporting the pelvic organs while simultaneously using a specific methodology to modify the tendency to tighten the muscles of the pelvic floor when under stress.Dr Jerome Weiss gives a perceptive explanation why humans may tense their pelvic floor in as a result of stress:

The pelvic floor responds to stress. As people with IC know, stress many times will exacerbate your symptoms. The mechanism of response can be understood when you look at a dog's tail. A dog's tail mirrors the emotions. When the dog is happy, the tail moves from side to side very loosely. When the dog is stressed, the tail pulls tightly between its legs. The pelvic floor muscles are the tail waggers. When men and women lost the tail (during evolution), they still retained the muscle structures. When we stood upright, they become supporting muscles rather than waggers. But, nonetheless, when humans are stressed the tail pulls forward ... the coccyx pulls forward. When it pulls forward, it compresses the organs that run through those muscles and it pulls them up against the pubic bone.It appears that this chronic contraction results in the muscle being overworked, which in turn results in the development of trigger points.

Although CPPS itself does not involve infection, bacterial prostatitis also appears to be another potential initiating factor in a small proportion of patients. Although a prostate infection may be successfully treated with antibiotics, the protective muscle spasm which accompanied the infection may overload the muscle, leading to the development of myofascial trigger points, which result in pain that persists long after the infection has cleared up. Physiotherapist Rhonda Kotarinos illustrates how a similar situation may lead to the development of the symptoms of BPS/IC:

A trigger point is an area of hyper-irritability in a muscle, usually caused by a muscle that is being overloaded and worked excessively. How does this affect an IC patient? Unfortunately, we do not always know what comes first; the chicken or the egg. Let's assume in this case we do. A patient who has never had any symptoms before develops an awful bladder infection, culture positive. She is treated with antibiotics, as she should be. Symptoms are, as we all know, frequency, urgency and pain on urination. Maybe the first round of antibiotics does not help, so she goes on a second round. They work. But she has now walked around for 2, maybe 3 weeks with horrible symptoms. Her pelvic floor would be working very hard to turn off the constant sense of urge. This could create overload in the pelvic floor. A trigger point develops, that can now cause a referral of symptoms back to her bladder, making her think she still has a bladder infection. Her cultures are negative.In the above scenario, the infection has cleared but a process of neural wind-up and central sensitization has occurred:

It is interesting that patients with IC (similar or identical to CPPS, but bladder-centred) and IBS both appear to be more sensitive to visceral stimulation than healthy people are (Buffington et al 2004). In patients with IBS, this sensitivity has been documented throughout the gastrointestinal tract. In humans with IC, awareness of bladder filling occurs at smaller volumes than in normal individuals, an observation confirmed by urodynamic studies. There appears to be a hyperresponsiveness of central stress circuits, mediating altered autonomic regulation and altered perceptual responses to visceral stimuli.

Other Triggers

Another frequently overlooked problem is abnormal pelvic and lower back mechanics. After a fall, accident or injury, the pelvis and lower back can be knocked out of alignment. If this causes the pelvis to become unstable, the pelvic floor may have to contract when it normally wouldn't in order to stabilise the pelvis. This too can obviously overload the pelvic floor and lead to the development of myofascial trigger points.Dr Weiss lists many other possible initiating factors, including "holding patterns and tensions in the bladder floor; brief overload from an accident, or fall, or sports injury; direct physical trauma from bike riding, childbirth or gynaecologic/urological surgery or instrumentation; inflammation, from urethritis, prostatitis, cystitis, endo and/or anal fissures; referred pain from other areas or the viscera".

For some as yet unknown reason, people who develop pelvic myoneuropathy are far more likely than the average person to suffer allergies, fibromyalgia, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and anxiety disorders such as panic attacks, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), etc.

Whatever causes the problem in the first place, the end result appears to be the same: The development of myofascial trigger points and accompanying sensitisation of the nervous system which results in pelvic pain and urinary dysfunction.

How do I know if I have Pelvic Myoneuropathy?

It is important to point out at this stage that there are many other factors which, whilst not common, could give rise to some of the symptoms of CPPS. It is therefore essential to see a urologist and be examined for any urological conditions such as strictures, UTI and bacterial prostatitis. Once these conditions have been either ruled out (most patients) or treated, it is then essential to have a full pelvic floor examination, which consists of two parts: a manual exam and a computerised EMG assessment of pelvic floor function.Leading prostatitis researcher Dr Daniel Shoskes states that "Based on the advice of Dr Rodney Anderson at Stanford, I now routinely palpate the pelvic floor muscles before palpating the prostate. In some patients, the muscles are readily appreciated to be in spasm, and pressure on them reproduces their pain".

Here Rhonda Kotarinos gives a detailed description how she completes a pelvic floor examination:

The pelvic exam has two components: an internal exam and a computerized muscle assessment. The pelvic exam is focused on assessing the musculature and other pelvic tissues not the organs. The pelvic floor, also know as the levator ani, is evaluated with regards to its function. Can the patient locate the muscle and perform an isolated contraction? Or does she use other muscle groups to assist her in contracting the muscle? This is also known as substitution. Is there difference from the right side to the left? Are there trigger points in the muscles? Trigger points can be a source of pain as well as cause the muscle to not function properly. The therapist will also assess the ability of the pelvic floor to relax after a contraction. The ability of the patient to do a lengthening contraction from the resting position is also evaluated. This is also known as an eccentric contraction. An eccentric contraction is the motion that is required to initiate urination. During the internal exam the therapist will also be assessing the other tissues found within the pelvis - the connective tissue and the neural tissue specifically. There are also other muscles inside the pelvis that are actually leg muscles. These are closely related to the pelvic floor muscle. So, if you traumatize a leg, you could set up a domino effect that could cause a pelvic floor problem. You need to monitor those muscles as well.

Besides the internal exam, there is also computer assessment. The computer assessment measures the force the pelvic floor muscle generates when it contracts and its range of motion. I utilize the computer to provide objective data to describe the pelvic floor changes as treatment progress.

Can Pelvic Floor Muscle spasm and Trigger Points be Treated?

The good news is that the answer to this question appears to be "Yes", although it requires a degree of commitment on the part of patients and a skillful practitioner experienced in trigger point assessment and treatment in the pelvic floor of men.Physiotherapy/Myofascial Release

Myofascial Release involves the physiotherapist "de-activating" trigger points in the pelvic floor and associated muscles by applying pressure to them. Some of this can be done externally, although to reach some trigger points the therapist generally has to access some points internally via the rectum. These techniques essentially consist of manually stretching the shortened muscles of the pelvic floor, encouraging them to "reset" at their normal length. Jerome Weiss published a paper (discussed here) in which these techniques were found to be very effective in the treatment of IC. It should be noted that the pelvic floor is intimately related to several pelvic ligaments and nerves, and physiotherapy may need to address these tissues also, as well as ensuring correct alignment/mechanics of the lower back and pelvis.Paradoxical Relaxation, or Using the Mind to Combat Pain

Psychologist Dr Wise states thatMyofascial release and competence in paradoxical relaxation of the pelvic floor are equally necessary in my experience. The myofascial/trigger point release releases the pelvic floor from its contracture while the relaxation training aims to end the habitual holding that started the problem in the first place. I tell patients this is the 'slow fix,' not the 'quick fix.' It is an inside job requiring the patients' steadfast efforts.Of "paradoxical relaxation" (a phrase he coined) he states

There is a trick to profound relaxation, but it's counterintuitive. You have to lower autonomic arousal in general. Specifically, you have to feel the contracture and actually open yourself up to the pain. I have measured EMG activity in the anus using a pelvic floor sensor and observed that the tension almost always reduces as a man adopts this strategy. I've had to redesign the language of relaxation instruction to communicate how to do this.

Kegel Exercises and Electrical Stimulation

Although pelvic floor contraction (kegel) exercises are sometimes suggested for CPPS patients, many of them report that these exercises significantly worsen their symptoms. Dr Wise also has a negative view of these exercises in relation to CPPS patients. Some research does suggest a potential role for electrical stimulation of the PFM in the treatment of CPPS, although Dr Wise has a similar view of the usefulness of this as a therapeutic option.Biofeedback

When talking about CPPS, the term "biofeedback" is sometimes confused with kegel exercises, but biofeedback simply relates to the patient receiving feedback about a biological function via a computerised screen. In the case of CPPS, patients can receive feedback about the tone of their pelvic floor muscles and can be taught to distinguish between tension and relaxation in these muscles. Some physiotherapists have reported success with this approach in combination with myofascial release, although it is important to state that the exact biofeedback intervention strategy must be based on the results of an individual's computerised pelvic floor exam; there is no one size fits all approach. This research has shown biofeedback to offer significant therapeutic benefit in the treatment of CPPS. However, Dr Wise has profound doubts about its usefulness for male pelvic pain patients.Pain Medications

Several pain medications also offer potential benefit to CPPS patients whose symptoms are caused by PFM spasm. Dr Shoskes states that he has "had success with Neurontin and Elavil in these patients".Until further research has been completed, it is impossible to state with any degree of confidence which type of treatment works best. It may be that an individually tailored combination of the above treatment strategies is ideal, although both trigger point massage and pelvic floor relaxation exercises appear to be the cornerstone of most successful treatment strategies.

Other Medications

The final effect of pelvic myoneuropathy is inflammation in the epithelial tissues of the urogenital region. This end point in the process may be treated with medications like Elavil, but also with phytotherapy: Prosta-Q†, Q-Urol† and Cernilton†. Benzodiazepines (the best of which for this purpose is Valium, generic name diazepam) are also used on a short-term or "as needed" basis to quell muscle spasm, in combination with hot baths. A dose of 5mg once every three days or as needed to avoid addiction is recommended.Locating a Practitioner

In an ideal world, you would visit a urologist who would carry out the necessary tests, including an assessment of your pelvic floor muscles, and who would then refer you to a physiotherapist specializing in the treatment of pelvic pain, and also to a pain specialist if necessary. Although there are some urologists who undoubtedly do this, the vast majority do not at present. That means that the task of navigating the healthcare system and getting the treatment you require is up to the patient, who will have to find a physiotherapist and get appropriate referrals. However, it is important that you find someone who can support and guide you in seeking out the most appropriate treatment. This may be a family doctor, urologist or pain specialist, but the most important point is that you need to find someone who is prepared to listen to you and learn about this condition. For example, taking one of the papers in the links at the end of this article to an open-minded and supportive family doctor might be a good starting point.Locating a physical therapist trained in these techniques can pose a challenge. At present, a comprehensive, international database of suitably qualified practitioners is not available. However, a simple approach is to use the yellow pages and call round physiotherapy clinics until you find a physiotherapist who is experienced and qualified in the techniques of myofascial release of the pelvic floor. Also, the UCPPS Forum (registration required) has a database of suitably qualified physiotherapists. Another option is to take some information to a physiotherapist you trust, who may have treated you in the past for another condition, and ask if he would be interested in learning the techniques of pelvic floor myofascial release. Many physiotherapists will be aware of the techniques involved -- they just have probably never applied them to pelvic floor myofascial pain.

For those who are fortunate to stay within travelling distance, the National Center for Pelvic Pain Research is offering an intensive program for the treatment of tension disorder prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Patients are initially accepted into this program after staff compare their symptoms to symptom profiles that indicate the possible diagnosis of tension disorder prostatitis. Treatment will take from five days to three weeks depending on schedules and staff availability at the National Center for Pelvic Pain Research. See here for more details.

In addition, the Wise-Anderson team provide training to physiotherapists in the treatment of pelvic floor myofascial pain. Dr Wise is also conducting a series of "Paradoxical Relaxation" seminars for patients. It is hoped that as this treatment protocol becomes more widely accepted, more physiotherapists will be trained in these techniques.

Further Reading:

Excellent additional information can be found in the book Headache in the Pelvis.

No comments:

Post a Comment